|

|

|

|

The Three Strikes Law: Fair and Effective?

|

| Richard Allen Davis |

October 1, 1993 is a day that will be remembered as the day California came down on criminals with a vengeance. Richard Allen

Davis, a criminal with a very long list of convictions, kidnapped and murdered a 12 year old girl on October 1, 1993. Davis'

crime was the momentum behind the Three Strikes Law. He is the prime example of why this law should be kept, because repeat

offenders should be kept in prison, instead of being released on the streets where they can prey on unsuspecting people.

In 1996, Davis went to court for his convictions, and was found guilty of 10 felony counts, including the main charge: attempting

a lewd act with a child under the age of 14. For these convictions, he was given the death sentence.

|

|

|

A convicted felon, with a past history of violence and sexual assault, was able to walk out of prison and commit this kidnapping/murder

just three months into his probation. Under the Three Strikes Law, he would have already been locked up for life with no

chance of parole. Almost every state in the U.S. has some form of the Three Strikes Law, but California;s is by far the strictest,

with good reason. California's crime rate is lower than it has ever been, our prisons are not overflowing as expected, and

the second strike provides a good deterrent to not commit crimes again.

|

|

|

Richard Allen Davis' extremely long criminal record:

March 6, 1967:

At age 12, Davis has his first contact with law enforcement when he was arrested for burglary in Chowchilla, where he

lived with his grandmother.

May 24, 1967:

Arrested again for forging a $10 money order. He was briefly in Juvenile Hall before his father moved him and his siblings

to La Honda.

Nov. 15, 1969:

Arrested for the burglary of a La Honda home.

Nov. 16, 1969:

The first of several occasions when Davis' father turns Davis and his older brother over to juvenile authorities for ``incorrigibility.''

September 15, 1970:

Arrested for participating in a motorcycle theft. A probation officer and judge accept his father's suggestion that he

enlist in the Army to avoid being sent to the California Youth Authority.

July 1971:

Entered the Army. His military record reflects several infractions for AWOL, fighting, failure to report and morphine

use.

Aug. 1972:

General discharge from the military.

Feb. 12, 1973:

Arrested in Redwood City for public drunkenness and resisting arrest. Placed on one-year summary probation.

April 21, 1973:

Arrested in Redwood City for being a minor in possession of liquor, burglary and contributing to the delinquency of a

minor. Charged with trespassing, later dismissed.

Aug. 13, 1973:

Arrested in Redwood City leaning against hedges extremely intoxicated. Released when he was sober.

Oct. 24, 1973:

Arrested in Redwood City on traffic warrants. Between April and October, he was implicated in more than 20 La Honda burglaries,

leading a probation officer to report that residents were so angry at him, he might be in danger if he returned to La Honda.

He pleaded guilty to burglary and was sentenced to six months in county jail and placed on three-years probation.

May 13, 1974:

Arrested for burglarizing South San Francisco High School. He is sent to the California Medical Facility, Vacaville, for

a 90-diagnostic study. A county probation officer recommends prison, but proceedings are suspended when Davis enrolls in a

Veterans Administration alcohol treatment program. He quits on the second day.

Sept. 16, 1974:

Sentenced to one year in county jail for the school burglary. He was allowed to leave jail to attend a Native American

drug and alcohol treatment program. He failed to return, leaving behind two angry fellow inmates who had given Davis money

to buy drugs and bring the contraband back to jail.

March 2, 1975:

After being released, the two inmates tracked Davis down and shot him in the back. He is rearrested on a probation violation

for failing to return to jail. Later, he testified against the inmates, earning him the epithet of ``snitch'' from fellow

inmates. He was placed in protective custody.

April 11, 1975:

Arrested for parole violation.

July 11, 1975:

Arrested for auto theft and possession of marijuana. Received 10-day jail sentence.

Aug. 13, 1975:

Probation revoked after arrest for San Francisco burglary and grand theft. He was sentenced to a term of from six months

to 15 years in prison.

Aug. 2, 1976:

Paroled from Vacaville.

Sept. 24, 1976:

Abducted Frances Mays, a 26-year-old legal secretary, from the South Hayward BART station and attempted to sexually assault

her. She escaped, hailed a passing car, in which California Highway Patrol Officer Jim Wentz was riding. Wentz arrested Davis.

Dec. 8, 1976:

Transferred to Napa State Hospital for psychiatric evaluation after he tried to hang himself in a cell at Alameda County

Jail. He later admitted he faked the suicide attempt in order to be sent to a state hospital, where he could more easily escape.

He was mistakenly admitted as a voluntarily patient rather than a prisoner.

Dec. 16, 1976:

Escaped from Napa State Hospital to went on a four-day crime spree in Napa. He broke into the home of Marjorie Mitchell,

a nurse at the state hospital, and beat her on the head with a fire poker while she slept. He broke into the Napa County animal

shelter and stole a shotgun. He used the shotgun to try to kidnap Hazel Frost, a bartender, as she climbed into her Cadillac

outside a bar. When she saw he had bindings, she rolled out of the car, grabbed a gun from beneath the seat and fired six

shots at the fleeing Davis.

Dec. 21, 1976:

Broke into the home of Josephine Kreiger, a bank employee, in La Honda. He was arrested by a San Mateo County sheriff's

deputy hiding in brush behind the home with a shotgun.

June 1, 1977:

Sentenced to a term of one to 25 years in prison for the Mays kidnapping. A sexual assault charged is dropped as part

of a plea bargain. He is later sentenced to concurrent terms for the Napa crime spree and the La Honda break-in.

March 4, 1982:

Paroled from the Deuel Vocational Institute in Tracy.

Nov. 30, 1984:

With new girlfriend-accomplice Sue Edwards, he pistol-whipped Selina Varich, a friend of Edwards' sister, in her Redwood

City apartment and forced her to withdraw $6,000 from her bank account. Davis and Edwards make a successful escape.

March 22, 1985:

Arrested in Modesto when a police officer noticed a defective taillight. He and Edwards were charged with robbing a Yogurt

Cup shop and the Delta National Bank in Modesto. Authorities in Kenniwick, Wash., were unaware for several years that the

pair had robbed a bank, a Value Giant store and the Red Steer restaurant during the winter of 1984-85. Davis later confessed

to the crimes in an attempt to implicate Edwards, whom he believed to have welched on a promise to help him while he was in

prison.

June 27, 1993:

Paroled from the California Men's Colony, San Luis Obispo, after serving half of a 16-year sentence for the Varich kidnapping.

Oct. 1, 1993:

Davis kidnapped Polly Klaas during a slumber party at her Petaluma home and murdered her.

Oct. 19, 1993:

Arrested in Ukiah for drunken driving during the search for Polly. He failed to appear in court.

Nov. 30, 1993:

Arrested for parole violation on the Coyote Valley Indian reservation north of Ukiah, he is identified as the prime suspect

in the kidnapping.

Dec. 4, 1993:

Davis provides investigators with information that leads them to Polly's body off Highway 101 near Cloverdale.

Dec. 7, 1993:

Charged with the kidnap-murder of Polly.

June 18, 1996:

Convicted of kidnap-murder of Polly.

August 5, 1996:

Superior Court jury in San Jose recommends death sentence.

.

|

|

|

|

|

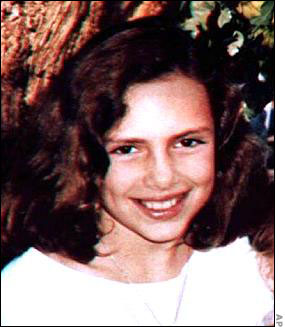

| Polly Klaas |

Proposition 184, the real name of the Three Strikes Law, went into effect in 1994, with an overwhelming majority of 72%.

There are many controversial issues over this law, including the imprisonment of mainly drug addicts or nonviolent offenders.

Make no mistake, the past two convictions a person had received must have been two violent felonies in order to be considered

as a strike; whether or not a felons third strike was nonviolent, he/she could have a history of violence that would make

a judge give the third strike.

Another misconception of this law is that it is extremely unforgiving. There is no exact number, but many judges will

lower the severity of nonviolent felonies to misdemeanors, reducing the sentence drastically from the 25 to year imprisonment.

There is evidence that this occurs often, but judges will review whether a felon has a past history of violence to convict

them appropriately. Despite this, California is the safest it has been in 10 years.

On that note, 2,000,000 less crimes were committed from 1994-2004, although there was a general trend of crime rates dropping

throughout the U.S. Despite this, California had the greatest drop in crime out of any city (47%), including New York, which

also had a substantial drop in crime (31%). According to Senator Chuck Poochigian, "In 1995, the California Department

of Corrections also predicted an explosion in prison population resulting from Three Strikes that would top out at close to

235,000 inmates in 2001. On June 30, 2001, California's inmate population was 161,497; 70,000 inmates fewer than projected

by Corrections. In fact, California's population growth slowed to nearly a halt within 5 years of the passage of Three Strikes,

and grew by less than 1% between 1999 and 2004.

As mentioned before, there was a general downward trend of crime throughout the nation from 1991-1994, and California's crime

rate in particular went down 10% during this time. Violent crime was reduced 43% from 1994 to 2003. According to the Legislative

Analyst's Office (LAO) report, "Researchers have identified a variety of factors that probably contributed to these reductions

in national crime rates during much of the 1990s including a strong economy, more effective law enforcement practices, demographic

changes, and a decline in handgun use." Despite these other factors, the Three Strikes Law has clearly deterred violent

criminals from striking again.

2005 LAO Report

Analysts also predicted huge growths in prisoners incarcerated, as well as a need for new prisons, but their estimates were

wrong. There were plans for 7 new prisons to be open, and the total capital outlay costs were $1.8 billion. Even though

that seems to be a large number, people convicted under the Three Strikes Law only make a portion of the entire prison population,

and these prisons were scheduled to be built before the passage of this law.

According to the 2005 LAO report, "The budget for CDCR has increased by about $3 billion since 1994-95, but much

of this growth can be attributed to costs unrelated to Three Strikes, such as increased medical costs and higher numbers of

parole violators returned to prison." The cost of housing these inmates is $1.5 billion annually, but LAO estimates

it to about half a billion a year, because many of the strikers currently in jail because of their third strike, would most

likely be in there for a different crime. However, the main reason the estimate of inmates incarcerated is so low, is that

judges will lower a past felony charge to a misdemeanor, thereby erasing a strike off your record and keeping it at 2 strikes.

As statistics show, the amount of inmates has increased, but the need for new prisons is nonexistent. Although there

are different methods to conserve space, prisons usually will have bunk beds 2 to 3 people high. This has effectively made

more room for inmates while allowing workers to not have to construct more prisons. Another benefit of having the Three Strikes

Law, is the deterrent effect of receiving a second strike. Many felons become scared at the prospect of 25 to life behind

bars, and think twice about committing a crime. Although this is beneficial, many criminals choose to leave the state to

continue their dirty work elsewhere.

The Three Strikes Law has prevented millions of crimes from being committed, putting away repeat offenders where they

belong: behind bars. California has the lowest crime in its history, our prisons are not overflowing, and the second strike

provides a good deterrent against future crimes. The Three Strikes law has singled out the repeat offenders in this state

who cannot seem to resolve their ways. It is indeed a shame that such petty crimes could warrant such harsh punishment, but

their past record is an indication that they could commit another serious or violent felony. However, I do believe the law

should be changed in terms of wording, because only violent criminals should be put away, and not nonviolent offenders.

In order to achieve such a goal, there must be a change in the wording of the law, so mainly violent or serious crimes

will be punished the most severely, while other petty crimes will not be considered a strike. The Three Strikes Law was a

very simple concept, but it has completely changed our criminal system. Despite negative feedback, the numbers do not lie;

California has never been safer in the past 10 years as it is now, with statistics far below the estimated average.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|